As our short Alaskan summer comes to a close, our work at Bird TLC slows but doesn't stop. And while the summer may have been short, it sure was busy.

Baby birds were the majority of Bird TLC's intakes from May-August, including over 100 orphaned waterfowl. We want to introduce you to our waterfowl-loving volunteers, Dave and Cindy Schraer, and highlight their incredible work.

A family of Green-winged Teals orphaned when their mother was struck by car.

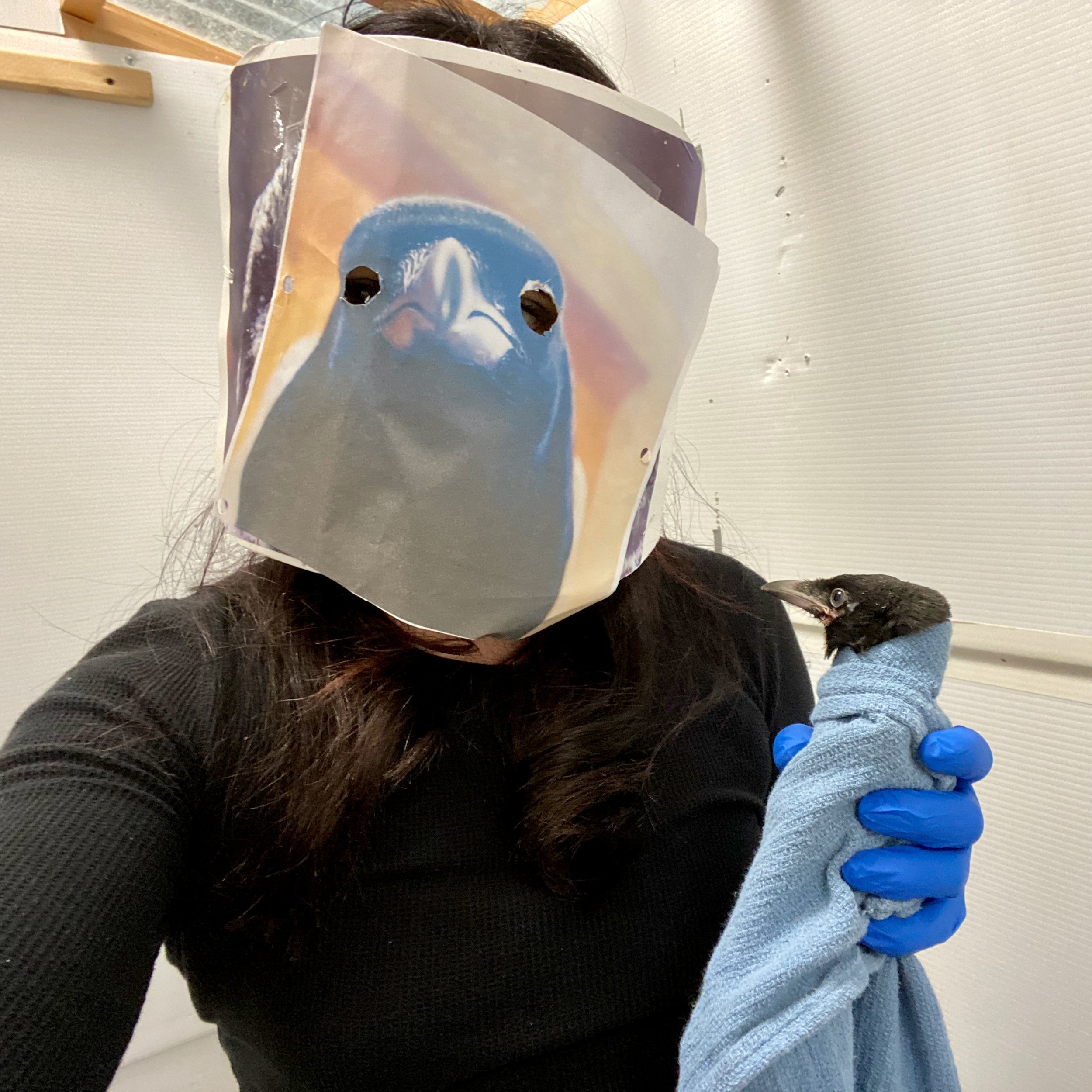

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) (Read about HPAI and Bird TLC's preventative protocols at the end of this post) has made caring for orphaned waterfowl challenging. Because waterfowl are asymptomatic carriers of HPAI, they are cared for in a quarantine area, allowing us to rehabilitate them safely and responsibly. This area has been affectionately coined "Gullville" by Dave and Cindy.

Dave has volunteered for Bird TLC for over a decade (since 2008!). He has worked with raptors, corvids, and songbirds and now specializes in caring for orphaned waterfowl. Cindy has volunteered at Bird TLC since 2019, getting her start by hand-feeding baby gulls. Now she's hooked on gulls!

The hard-working Schraers, both retired doctors, are invaluable volunteers who manage the set-up and running of Gullville throughout the summer with the help of other volunteers and staff. They are involved with every step of caring for orphaned waterfowl - from the initial care to release back into the wild. They spend their days cleaning, feeding, and monitoring the health and behavior of each of their charges. At the height of the season, the Schraers can have up to 60 baby birds at once!

Cindy and Dave estimate that in the summer of 2022, the first year of HPAI, they worked 8-10 hours daily in the waterfowl quarantine area. But before the waterfowl arrived, they spent a month and a half constructing the quarantine area with the assistance of other volunteers and staff. This year, they were grateful for additional help from the Alaska Chapter of the America Zoo Keepers Association.

Operating Gullville, as Cindy describes, is no easy feat; it requires a lot of work physically, mentally, and emotionally, but the reward of releasing rehabilitated young waterfowl into the wild makes it worth the effort to them.

An orphaned Common Goldeneye and Canada Goose gosling cuddle together.

We can't begin to express how much we appreciate all the Schraers do for Alaska's wild birds and Bird TLC.

Next month, we’ll meet the volunteer who raises baby songbirds.

About HPAI and Bird TLC's preventative protocols:

HPAI is a highly contagious and tough virus that can survive freezing temperatures and remain viable in aquatic environments. Raptors, like Bald Eagles, are highly susceptible to contracting the virus.

With the significant outbreak of HPAI in 2022, many avian rehabilitation centers across the country temporarily closed their clinics or stopped admitting waterfowl to keep their resident education birds safe from the virus. Waterfowl are asymptomatic carriers and can pass the disease to other birds simply by shedding the virus in their saliva, nasal fluids, and feces.

Bird TLC has remained open to all species of birds throughout the HPAI outbreak. We implemented and continue to follow strict protocols to keep our Ambassador Birds safe and prevent the spread of the virus from an infected wild bird to an uninfected bird.